I don’t consider myself a fashionista, but I’ve always been a fan of fashion. I grew up watching Project Runway, have often ogled over fashion magazines and fashion blogs, and window shop on a fairly regular basis. Over the years I’ve developed a healthy interest in trends and incorporating those trends into my style (within reason of course).

One of the trends I remember during my high school years was the Carvela trend. I remember there came a stage when I saw the Italian shoes, often worn with floral shirts and pants that came just above the ankle, everywhere. They were a shoe of choice among Kasi boys and became a hallmark symbol of the izikhothane subculture. They, and the people who wore them, were subjected to serious mockery by my friends and me. We viewed the shoes as “ugly” and most importantly as “ghetto”. We were not alone. Across the board, both on and off social media middle to upper middle class black kids, among others, relentlessly mocked the shoes. We decried them as shoes we would never be caught dead wearing, and if you cared at all about your image you made sure you weren’t.

Fast forward to 2016 and fashion brand Spits in collaboration with Carvela has launched their South African #LoveMyCarvelas campaign using popular twelebs and young fashion influencers as their models. Over the past few days, photos of them wearing the once derided shoes have hit Twitter by storm portraying the shoes, and their wearers in a Pinterest/Tumblr-esque high fashion aesthetic.

The campaign has received a mixed reaction. On the one hand, there are those praising it for “broadening the target market” of Carvelas and portraying the brand in a fashion forward, “classy” way. On the other hand, there are a number of uncomfortable truths one is confronted with by the campaign. The first is that, contrary to what we believed and insisted in high school, the shoes are not in any way ugly. In fact, even back then we were wearing these exact same shoes but we weren’t calling them Carvelas nor were we buying the actual brand. We were buying other brands of the exact design and calling them “moccasins” or “loafers” or by whatever other official fashion term existed for them.

The design itself was fine, the brand was not. This then leads us to the second uncomfortable truth: there’s nothing actually wrong with the brand. What was wrong in our minds was the people who were associated with it. Without even realising it the deep seated classist attitudes we held manifested itself in a hatred and derision of anything associated with the “Kasi” lifestyle. A lifestyle that we, who were growing up and attending school in the cushy suburbs, wished to distance ourselves from at all costs. I can almost guarantee that had this campaign surfaced while I was in high school, there is a very good chance my friends and I would have marched to the nearest mall to purchase our very own pair of Carvelas. That is where the problem lies.

What makes this campaign particularly uncomfortable is the manner in which (as many on Twitter have rightfully pointed out) it completely erases its core market. For years, Kasi kids have been dedicated patrons of the brand and have made a significant contribution to the brand’s success in South Africa. Yet this campaign focuses firmly on the so-called “Cool Kids”, the black fashionistas who are native to hipster havens such as Braamfontein, Maboneng, among others. The aesthetic of the black “Cool Kid” is one firmly rooted in the middle and upper middle class, making it highly marketable for brands such as Carvelas and exclusionary to those who have in many ways popularized it within South Africa in the first place. I, and many others, may never have even heard of the brand had it not been for the izikhothane subculture.

The uncomfortable truths behind the campaign bear some similarities to the fashion industry in the US and its endless appropriating of African American culture. Over the decades, African Americans have been derided for the manner in which they dress, style their hair, dance, speak and the music they produce and listen to. Yet at the same time, this exact culture has been reproduced in pop culture from the rise of white musicians with a notably black sound such as Eminem, Justin Timberlake, Adele, and Sam Smith, to the Kardashians who are praised for having the very same black features often insulted when they are on black bodies, to the fashion industry labelling African American inspired clothing as “urban”, placing it on models who are not black and then selling it as high fashion.

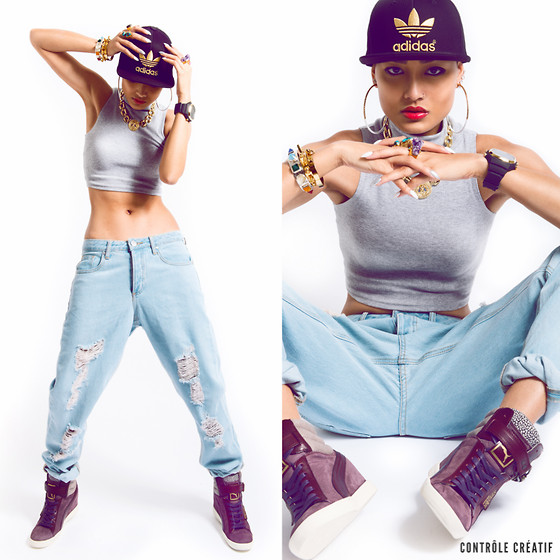

Micah Gianneli modelling African American inspired “Hip Hop” fashion for a high fashion label

In other words, the Carvela campaign is reproducing the tendency of the fashion industry to sell a “look” that was either created or popularized by a specific, often marginalised, group of people while simultaneously excluding them in the process. Sure, Carvela could perhaps argue that this is their brand and they had never intended to be associated with the izikhothane subculture in the first place. But this would miss the point entirely.The brand has ignored its most faithful core market to pander to a far more fickle one which may wear its shoes today and move on to the next hottest trend tomorrow all as it often does. In an attempt to distance itself from its association with the izikhothane subculture, the brand has reproduced the same latent classism that we did in back in high school.

EXCELLENT and nuanced look at the Carvela issue

LikeLike

Dope article

LikeLike

nice article. we definitely see this over in the US a ton and im so glad that the issue of appropriation is getting the play within the fashion industry it deserves

LikeLike